Local film featured at SLO International Film Festival

Steinbeck documentary showcases history of local family and property

Heritage Steinbeck: Honoring Family, Cultivating Land, Touching Lives. from Kathy Kelly Productions, Inc. on Vimeo.

Editor’s note: Local film producer Kathy Kelly created a documentary of the Paso Robles Steinbeck Vineyard property and family. It was selected to be screened at the 2014 SLO International Film Festival this Sunday, March 9 at 1 p.m. Below Kelly tells the story of making the documentary.

Making the Steinbeck documentary: The story behind the story

By Kathy Kelly

The scene on the Steinbeck Vineyard property where a B-26 bomber crashed in 1956.

It’s not often that a commercial marketer/TV producer gets the opportunity to produce a documentary, a genre that I feel is highly informative and engaging, yet, greatly under-appreciated. In fact, the last documentary I produced (prior to this recent work) was a joint project between MGM and EMI/Capitol Records celebrating the 30th Anniversary of the famed movie, Fiddler on the Roof, back in 2002.

In film and television, there is always a story behind “the story.” For example, the process I went through in the 2002 documentary, including getting interviews with actors and creators, employing new music tracks, using footage that didn’t make it into the film in addition to rarely-seen production photos, revealed a unique perspective to Fiddler on the Roof for me and to viewers of that prime-time TV special. The same is true in the making of my most recent documentary project: Heritage Steinbeck: Honoring Family, Cultivating Land, Touching Lives.

Since first meeting Cindy Steinbeck in the fall of 2007 I’ve learned a lot about the Steinbeck family’s seven-generation history. I discovered that they planted vines as far back and 1884, were instrumental in the early growth of the Paso Robles wine and grape-growing industry and I learned the story about “The Crash,” when, in 1956, a B-26 bomber crashed on their property and the miraculous survival of four out of five airmen on board. Often I would say to Cindy “Your family has a great story that needs to be told.” Five years later, Cindy gave me the opportunity. From it, I not only learned the heritage of a great family, but developed great pride in knowing them and being chosen to tell their story.

The original Geneseo School house.

It was a tall order. Cindy wanted a video to present to their Heritage Club members at their annual dinner in September. It had to tell about seven generations of family farmers, starting with the emigration from Alsace, Germany (now France) to Geneseo, IL, to escape war-torn Europe. It should include a fateful decision to move from Geneseo, IL to resettle and name in Geneseo, CA where the family started farming and built a schoolhouse. It had to honor the military, including their own family members who served. And of course, the video had to mention the 1956 crash of the B-26 Bomber and how the Steinbecks re-connected with the survivors. Perhaps most important, we had to explain the family’s long history as wine grape growers since 1884, how they overcame hardships along with way, why they launched the family business and when they realized it was time to add winemaking to their long grape growing timeline. All of this had to be told in 15 minutes! Yikes!

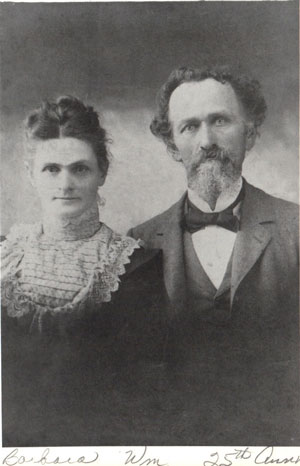

Steinbeck family ancestors Barbara and William Ernst, 1895.

At our first meeting she handed me two items. One was an old letter from Lieutenant Robert Nilsson to his parents, just days after surviving that B-26 crash. The other item was the memoirs of her great, great grandmother, Barbara Amelia Ernst (1st generation in America). These memoirs covered Barbara’s early years in the Alsace region of France (Germany at the time) up to the time when she established a homestead and Lutheran community in the Geneseo area next to Paso Robles. Rich with details and historic perspective, I knew these two first-person narratives would be central to the story.

Cindy scanned and provided over two hundred precious black and white family photos, many of which were torn, scratched, creased and faded, along with seemingly thousands of more recent family photos and early family videos. All this material was great, however, photos and old silent movies alone do not make for a very captivating or interesting presentation. Despite the volume of material in my hands, I knew I needed something more. I needed people who could tell the story from their perspective, just as I had done with the Fiddler documentary. I needed Cindy’s parent’s, Howie and Bev, Cindy herself, and others, to get in front of the camera and express their feelings about the family history. The challenge, however, was to get a survivor from the famous bomber crash also on camera. I realized I was about to embark on making another documentary, not a 15-minute family video.

Making a documentary involves a lot of thought, planning, time and, most of all, research. Of course, it has to start with a good story, but it takes thinking in a sort of third-dimension to put it all together. When writing a story for print, moving images and sounds are left to the imagination and interpretation of the reader. Writing for the screen, however, requires shooting, creating or acquiring visuals that tell or enhance the story. It requires getting on-camera talent, voice over talent, graphics, animation, music and sound effects that help move the story, make it interesting, and match the emotions of the storyteller.

When Cindy told me that Orazio Fazio, one of the two remaining crash survivors, was still alive, coherent and living in Boston, I knew I had to interview him. I was already planning a trip back east to see my in-laws in New York and visit my family in Boston, which is where I grew up. So, I contacted the long-retired Sergeant Fazio. Fortunately, he was more than happy to invite me to his home so he could re-tell the accounts of the crash, 57 years after it happened.

I loaded my Canon D5100 DSLR camera, tripod, one light and stand, a lavalier lapel mic and receiver, extra batteries and an extension cord and headed east. This was the smallest production and equipment package I have ever travelled with! I fit all the gear into one shoulder bag! Today’s compact and high-resolution technology makes doing remote shooting so much easier than it used to be.

I headed north to a small town about 40 minutes northwest of Boston on a rainy New England summer day, which meant I would have to shoot indoors. As I drove down his quaint street of 1959 homes, it didn’t take long to confirm I was at the right house, as I spotted his car’s special-issue “Veteran” license plate.

Meeting a man named Orazio Fazio was everything a name like that conjured up in my mind. He was a slight, Italian man, 89 years old, with the grin of a Cheshire cat and eyes filled with decades of life experience. His home was a small, humble split level Cape Cod-style, cluttered with knitted doilies and plastic flowers, and the smell of pipe tobacco permeating the house. In fact, the tobacco was so totally absorbed by the furniture, Fazio’s favorite chair, an ‘80s mauve, winged-back Queen Anne, was stained from tobacco smoke everywhere except for the clean silhouette formed by his body where smoke couldn’t reach.

Along with Fazio, as I have come to endearingly call him, his wife, son and constantly-talking parrot were all there, ready to pitch in–and they did! The parrot wouldn’t shut up! And his wife, listening from across the room, would help out in her own way by yelling out more details for her husband to include in his interview. Their son removed the noisy bird, and his wife sat quietly after I explained that she couldn’t talk until I said, “cut.”

Still, we had audio problems. There was a buzzing sound in the audio track. So, I tried shutting off the room air conditioner. Noise still there. I tried new batteries in the microphone. Noise still there. Finally, we found an air purifier (obviously, not an effective one) in the corner of the room that was on causing the noise. Now I was ready to roll.

The interview with Fazio was amazing. He remembered every detail of that day like it happened the previous week. He remembered what he was doing the morning he got the orders for the flight, where he was positioned on the plane, and what the pilot said when things started going wrong. He also got emotional when telling me how grateful he was when he realized he survived such a tragic accident. The interview was so good, I felt it would become a key element in the documentary. I started thinking about getting stock footage of a plane flying through clouds and stormy weather, but, I had no idea how I would re-enact a B-26 bomber crash. That’s where relentless research comes in.

With some luck, I found 1950‘s era photos of the same Air Force Base the flight originated from in Tucson, AZ. I also discovered a B-26 Bomber military training film that was made back in the 1950’s. Then I searched for, and found, dynamic black and white footage of airmen parachuting to safety. Finally, two original images from the actual plane crash were given to me by Cindy and I included them, too. Now I knew I had enough images to re-create “the crash.”

A week after shooting Fazio, I shot the majority of the show on two consecutive days in Paso Robles with three cameras, a Go-Pro and a small crew. The days were scheduled very tightly, as the first day included three location moves for most of the remaining eight interviews. The second day had a few interviews, but mostly “B-Roll”, which is video of supporting material, either with or without natural sound. The shooting days were two of the hottest days in Paso with temperatures reaching 115 degrees. Each day was a non-stop, 12-hour day with only 20 minutes for lunch, lovingly prepared by Bev Steinbeck for the crew.

For those who think production is all glamorous, it’s not. It’s hard and exhausting work, especially when you have little to no crew at all. In LA, for a video shoot of this magnitude would normally have 15-35 people on set. For this shoot, we had only three experienced production people: myself (producer, director, camera operator), Mike McGuffin, (Director of Photography, camera operator, grip/gaffer, sound) and Troy Abram (gaffer/grip). We each wore many hats. Mike also brought his two teenage sons along as production assistants/grips/camera operators and I roped my husband into working as the digital technician. His job was to manage all of the media.

After each interview all of the footage from three cameras had to be loaded onto the computer, copied onto a back-up drive, and then re-formatted to be ready for the next interview. Keeping all the media straight was critical. An entire interview could have been thrown away if each step was not taken in the right sequence. Yikes! That is one of the major differences between shooting film or video, like in the past, and shooting digital today. Film or video gives you reels or cassettes of tangible source material, precisely labeled and held safely in a suitcase or container. With digital, a day’s worth of shooting is reduced to a bunch of pixels on a 1-inch square card! So easy to lose or mess up!

I had written all of the interview questions in advance and crafted them so they would intertwine with each other for good story flow. As each interview was conducted, I began to see in my mind how the story would be edited. Each interview was awesome. For non-professional, on-camera talent, everyone came across naturally and articulate. Often, when you shoot people who are not used to being on camera, you don’t get good, usable footage. I was so happy with everyone that we shot. With this much good footage, I now knew that this documentary had to run longer than 15 minutes!

After shooting, while Mike was changing footage into a usable format that the editing system can read and manipulate, I had all of the interviews transcribed. I would use the transcription to start writing the script. While waiting for the transcripts, and with all of the interviews still fresh in my mind, I started outlining the documentary sections on a white board, which gave me a clear, visible form of structure and flow. It is at this point I decided to use the Fazio storyline as an “interstitial” throughout the whole movie–that is, I would weave his interview in and out of the Steinbeck story.

Next, was editing. With the script as our guide, we laid down a “scratch track” (temporary voices for narration, great, great grandmother, Barbara and additional crash survivor, Lt. Nilsson). Once we edited the first rough cut, it timed out at 45 minutes! I had some cutting to do. Sadly, we had to lose some stories, carefully cut some phrasing without losing meaning to the story, and tighten every breath. By the time we were done, we got it down to 32 minutes, with the story still clear and all the elements that Cindy wanted.

There were still many holes or temp images, though. The motion graphics still needed to be created to the timing of the rough cut, professional voices needed to be cast and recorded, music needed to be searched and selected, sound effects needed to be found or created and the whole show needed to be mixed and color-corrected. I shot several more days getting additional B-roll at Steinbeck, Eberle, and Justin wineries and also around town to get the finer details. I also visited the Paso Robles Pioneer Museum and Historical Society to get images that were mentioned by the narrator or by interviewees.

Now, it was time to show Cindy the rough cut in case she wanted to change anything. Reading a script is one thing, seeing what was written on the screen is another thing. Changing a single element in a rough cut can cause a ripple effect in the whole show, so, I was hoping that all would be approved and I’d get the green light to continue. Cindy sat there silently and watched every frame with great interest. Thirty-two minutes later, she didn’t move or say a word. She just sat there with a tear in her eye. Finally, and thankfully, she said, ”I love it!”

With Cindy’s blessing, I could start getting down to finishing touches. I cast the voices of Lt. Nilsson and Barbara Amelia Ernst through an online voice casting website. This allowed me to search among voices from all over the world. I wanted an authentic-sounding German accent in a woman who sounded like she could be 15 or 16 years old–the age of Barbara when she first moved to the United States. The voice I found was a woman from Germany, who lived close to the same France-Germany border area where Barbara Amelia actually grew up! What are the odds of that? For Lt. Nilsson, I wanted a young-sounding male voice, tough sounding, yet with some compassion. I found an actor out of Portland, Oregon. Since the budget would not allow a trip to Germany or Oregon to direct the recordings, I had each of them record several “reads” for me online and we mixed and matched the best takes.

For music, the budget also didn’t allow for original scored music, so I searched for nearly a week in music libraries for over 20 “tracks” of music that would fit the tone and mood of each scene or transition. Each segment of music I used had to also work with music that preceded and followed it. That was a time-consuming and painstaking process. We “auditioned” many pieces of music to make it feel like they all worked together.

Another element that added dimension to the movie were the sound effects. This helped bring all of the still shots and old silent film and videos to life. For that expertise, I called on a longtime friend and business colleague, Roy Braverman, who does a lot of work on cartoons in Hollywood. He is a master at finding or making the right sound effect for any scene. As we would complete sections of the show, Roy would send us various sound effects to apply. The real work, though, came when we got into the mix session and really focused on the sound effects with the final edited rough cut. By the time we were done, we had over 60 tracks of sound layered into the show. Once all of the sound effects were in the timeline, Roy and I worked until 3AM one morning to finish mixing all of the tracks together.

For the motion graphics, I used a designer, Shawn Sedoff, out of Houston Texas. I had just finished another project with him and loved his work. I drew sketches or found examples online of the how I wanted the graphics to look. There were a lot of graphics, so, to keep things on schedule, each animation sequence was sent to us in a low-resolution version as he created it. This allowed us to test it for timing. Once they were tweaked to match timings, they were rendered in high resolution and dropped into the show.

The final polish on the show was color correction. This is the process where you correct the color in each scene so that it all looks like a coherent piece. With three cameras that didn’t match in color temperature, all sorts of old black and white and sepia-toned images, various stock footage, photographs and animation, everything had a different color to it. The color correction really gave it a finished look.

With moments to spare, we dropped in the color-corrected footage into the timeline and mastered the show. The movie was shown just hours later at the annual Steinbeck Heritage party on a homemade large screen inside a vintage barn on the property to an audience of around 100 guests. The film was warmly received.

After the screening, the next day I felt kind of sad. The project was over. This baby that I conceived, nurtured and worked on for over four months was now on its own. After sitting in an edit bay for so long, getting to know my main characters so well, they become my friends. The project was over and it was like my friends had moved away.

I loved working on telling this story. I feel closer to Cindy and all of the Steinbecks as a result of it. And I am honored to be the one she asked to put it on the screen.

I’m also honored that Heritage Steinbeck: Honoring Family, Cultivating Land, Touch Lives was selected to be screened at the 2014 SLO International Film Festival on March 9th at 1PM. One family, seven generations and one hundred thirty years of heritage is captured for all to see. It deserved more than a video. It demanded the tried and true form of storytelling known as a documentary.